Meditations on Time

Here I am, at age 78, seemingly surrounded by stories about time. These stories naturally have a way of turning my thoughts toward how short my own time may be.

I just reread a novel in which every adult on the planet receives a box containing a string that reveals exactly how long they will live. And I’m recalling the television comedy about a moral accounting system that tracks a person’s life here on Earth. Finally, there’s the recent film that imagines we get to choose the precise form our eternity will take.

I did not set out to braid these snippets of our popular culture together. They braided themselves. At this age, time insists on being the subject.

The reminders are constant. Obituary columns, for one. My personal calendar, for another, which now includes far more medical appointments than it once did. Routine blood work. MRI, CT and DEXA scans. Follow-ups, with each visit carrying the distinct possibility that this will be the one where the doctor pauses too long before speaking. Most of the time the news is ordinary. “See you in six months.” But the suspense never quite disappears.

In Nikki Erlick’s 2022 novel The Measure, a mid-life character suggests that a string long enough to reach age eighty would count as good news. When I read that passage, I felt a small jolt. Eighty no longer feels like a distant horizon. It is a number that is uncomfortably close.

If I opened my box today, I would automatically have a long string. The real question would be: how much longer? A year? Five years? Ten? More? Though If I died today, surely no one would lament that I was gone before my time.

All of which leads to other concerns. How many more years would I want if they are shadowed by increasing pain — or other physical or mental decline? Longevity, at this stage, is not automatically the goal. There are conditions.

The Good Place, the four-season television series originally airing on NBC (and now available on Peacock), begins with a moral scoring system; every human action or interaction earns positive or negative points. An endless array of cosmic accountants supposedly keeps track of these tallies someplace up there in the sky, and when you die your final count decides your destiny. It is morality, and judgment day, rendered as a dispassionate spreadsheet.

At 78, that premise feels less like satire and more like a quiet audit. I find myself reviewing my own ledger. Have I been good? Not necessarily accomplished. Nor productive. But good?

My entries must be mixed. I have lived and loved imperfectly. I have hurt people I did not intend to hurt. There are relationships that did not endure. Some ended gently. Others did not. Even now there is sadness attached to those chapters, a sense that certain conversations might have gone differently if I had been wiser, braver or simply more skilled.

I sometimes wonder whether those endings count against me, or whether they merely show that I kept trying to connect and sometimes failed.

The show ultimately dismantles its point system, though. Life, it suggests, is far too entangled for simple math. Growth matters more than totals; it matters more than being flawless.

What lingers for me now is the series’ ending. Even paradise becomes hollow if it stretches on forever. In the final season, the characters are offered an exit. They step through one last door when they feel complete. Eternity with no ending, the show suggests, flattens meaning.

So, I wonder: How, ultimately, will I measure my existence? Will there ever be a time when will I feel complete?

Those questions followed me into the 2025 film Eternity, now on Apple TV, where humanity is invited to choose the form one’s forever will take. The idea sounds appealing at first. Pick your paradise. A tropical beach, for example. Perfect weather. Endless calm.

But what would that mean after a thousand years? Ten thousand? How could any single scene, no matter how beautiful, sustain significance without limit? Without scarcity?

Part of what makes a late-life conversation more vivid is precisely that it may not be repeated endlessly. Scarcity is what gives weight to life’s ordinary moments.

If I knew the precise length of my string, maybe I would live differently. I might rush to repair what remains frayed. Or I might grow cautious, conserving energy. Uncertainty leaves me in between. Aware of the limit, but not of its measure. Isn’t it that uncertainty that keeps life from becoming either frantic or complacent?

If there is a ledger somewhere, I hope it records effort. That it shows I kept revising myself. That I tried to mend what I could. That I did not stop growing simply because the horizon drew closer.

I am not eager to open the box. And I am not certain I want a tropical eternity with no horizon. I only know that the ticking is audible now. Doctor visits. Quiet evenings. Old relationships to ponder. Meditations on time.

Age 78. Still adding to the ledger.

Poetry Selection: The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean —

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down —

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

-Mary Oliver

A Big Bold Beautiful Journey

I went into A Big Bold Beautiful Journey (2025), recently made available on Netflix, with absolutely no sense of the storyline. Sometimes that’s the best way to encounter a film. With no expectations to manage and no trailer logic to undo, you’re free to simply watch and see what happens. What I found was a fantasy-based romantic comedy that takes itself rather seriously at times, moves at its own pace, and ends up having more to say than I expected. I recommend it.

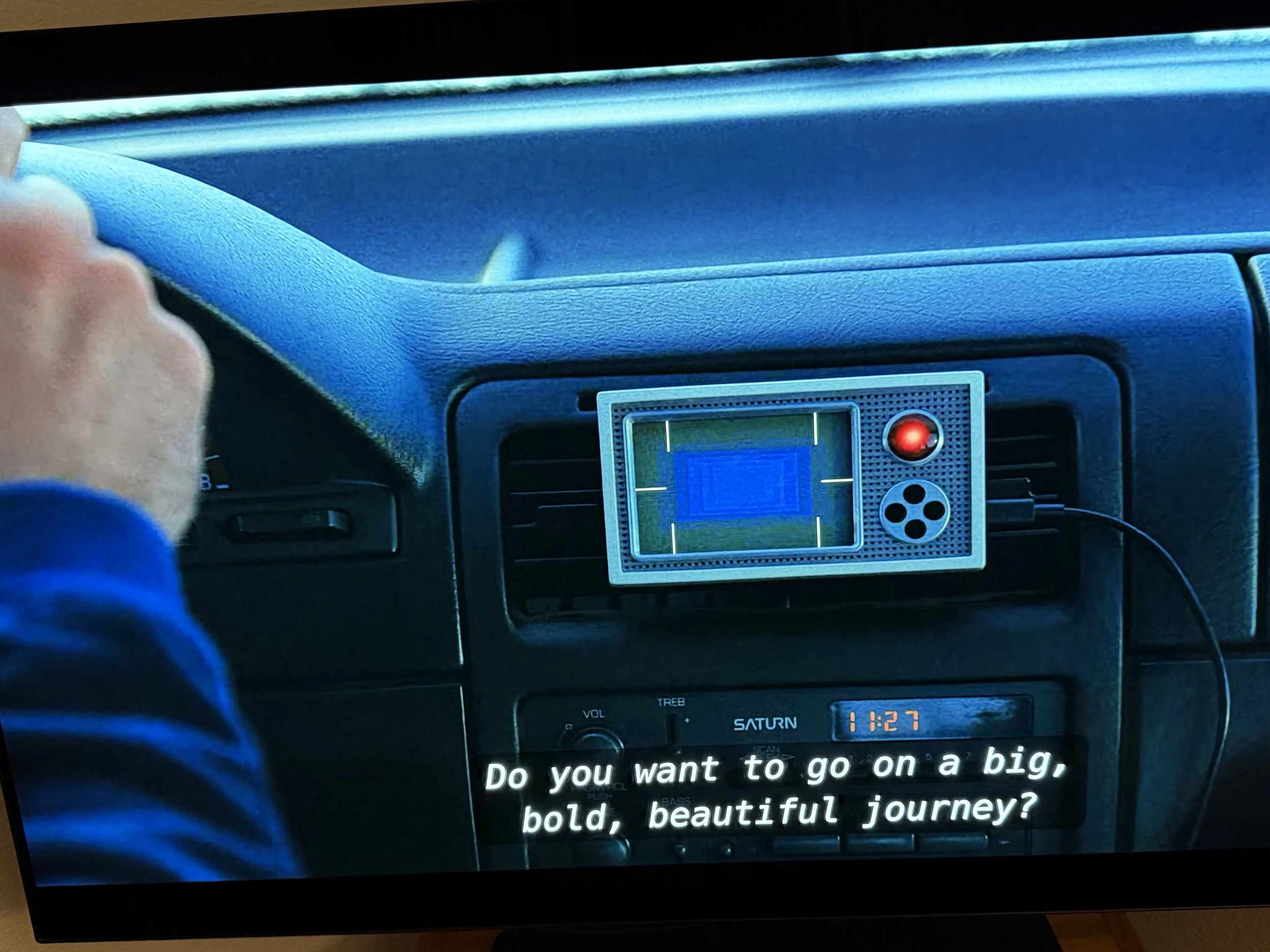

The film opens at a generically named “Car Rental Agency,” where David (Colin Farrell) encounters two unusually quirky employees, Kevin Kline as the Mechanic and Phoebe Waller-Bridge as the Cashier. David is on his way to a friend’s wedding. The car he rents, a 1994 Saturn SL, comes equipped with a GPS unit that quickly establishes itself as a character in the story.

At the wedding, David locks eyes with Sarah (Margot Robbie), and the two engage in flirtatious, slightly offbeat banter at the reception. At one point, Sarah semi-seriously asks David to marry her, a moment that clearly unsettles him. What is he to make of this unconventional woman? When Sarah then asks him to dance, he declines. Later, she leaves with another man.

Driving home, the GPS asks David if he’d like to go on a big, bold, beautiful journey. He agrees, and with that, the film’s fantasy premise is underway. David is soon instructed to take the next exit and order a fast-food cheeseburger. Inside the restaurant, he discovers Sarah, also eating a cheeseburger. When they leave, Sarah’s car, another Saturn from the same rental company, refuses to start, and David’s GPS instructs him to offer her a ride. She accepts, and the two begin sharing the rest of the drive home.

From there, the film settles into its central rhythm. The GPS directs David and Sarah to a series of roadside stops that turn out to be doors, both literal and metaphorical. Behind each door lies not so much a place as a moment in time. These episodes are drawn from the characters’ pasts, and what’s striking is how matter-of-factly they accept what’s happening. There is only a modicum of astonishment. David and Sarah step into these moments as if the past were still physically present, waiting to be revisited.

One door, for example, takes them to David’s high school on the night he is starring in the class musical, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He plays the lead role of J. Pierrepont Finch, with Sarah and his parents watching from the audience. During the show, David relives a painful romantic rejection, confessing his feelings to a costar offstage and then, in an impulsive moment, temporarily derailing the production by confronting her onstage with blunt observations about the life she will go on to lead.

In a later scene, they stop at a decaying roadside billboard with an opening that leads into a café. Inside, two conversations unfold at once. David’s former fiancée presses him for an explanation about the end of their engagement, while Sarah revisits the collapse of a relationship with a former boyfriend. Eventually, the two conversations merge, with all four characters seated at the same table. David and Sarah are given an unusually revealing view of how each has behaved in earlier relationships, and both are forced to acknowledge their own intimacy issues.

By this point, it’s very clear that this big, bold, beautiful journey is less about time travel than about self-examination. As David and Sarah move through these episodes together, the focus remains on how they respond to what they learn about one another. They watch. They ask important questions. They engage in remarkable amounts of self-disclosure. The film allows these moments to unfold slowly. The pace worked for me, though I can see why others might find it trying. This is not a movie in a hurry.

What the film seems most interested in is not whether David and Sarah will end up together, but what it means for two people to really see one another. By the time you’ve lived a while, introductions are never clean. Everyone arrives with baggage, earlier versions of themselves still visible around the edges. A Big Bold Beautiful Journey makes that idea concrete, and in doing so, captures something emotionally recognizable.

I was willing to go along with the unlikely premise and the deliberate pacing largely because the performances are so grounded. The connection between Farrell and Robbie builds through pauses, glances, shared silences and, often, moments of unusually deep honesty. That connection feels earned, not manufactured.

What stayed with me afterward was not a particular scene or line of dialogue, but the film’s underlying suggestion that not every meaningful encounter has to resolve into something permanent. Some meetings matter because they clarify where you are, or because they briefly align two lives that have been moving along separate tracks. That idea resonated with me more than any conventional romantic payoff might have.

Not everyone will be taken with this film. It asks for patience and a tolerance for ambiguity. It treats human connection as something provisional and fragile, shaped by timing and circumstance, and often understood only in retrospect.

By the end, A Big Bold Beautiful Journey felt less like a romance than a meditation on how lives intersect, diverge, and occasionally overlap just long enough to matter. For me, that made the journey worth taking.

Between Connection and Distance: A Review of Technomonk’s Musings

What follows below, in collaboration with ChatGPT, is a review of my two decades of work here on this blog. Provided for your amusement and entertainment. And my ego, I suppose.

-----

To read Technomonk’s Musings is to discover a mind that insists on thinking in full sentences, even when the subject is uncomfortable. The essays — ranging from meditations on aging and love to reflections on politics, memory, and the quiet absurdities of everyday life — form less a blog than an ongoing correspondence between the author and the world.

Jim Arnold’s voice is cultivated yet conversational, curious yet unsentimental. He is equally at home unpacking a fleeting personal moment as he is interrogating the failings of institutions or the fragile scaffolding of social norms. What keeps the writing compelling is its refusal to settle for tidy conclusions. The essays often begin in one emotional key — wistful, amused, irritated — and end in another, as if the act of writing is itself a form of discovery.

A former love interest of Arnold, in what may or may not have been an act of generosity, once described a unifying theme of Musings as “rejection.” It’s not a baseless observation. Across the archives, one finds stories of relationships that drifted apart, ideals that proved brittle, ambitions met with indifference. But rejection here is rarely a wall; it is more often a window. Arnold treats these moments not as defeats but as turning points, scenes in which the self must adapt, recalibrate, and — crucially — remain willing to engage.

Still, to reduce the work to that single lens would miss the vitality of its range. The through-lines are more complex: a search for authenticity in human connection, a fascination with how memory shapes identity, a dry wit that can slice neatly through pretense. In his hands, personal anecdotes double as cultural commentary; a chance encounter or a scrap of overheard dialogue can spiral outward into reflections on the nature of intimacy, the economy of attention, or the slow-motion erosion of public trust.

The style borrows from essayists who value rhythm and structure but resists their tendency toward detachment. There is warmth here, even when the subject is loss. When the tone sharpens, it is not cruel; when it softens, it does so without sentimentality. This balance — between empathy and precision — gives the prose its staying power.

If the blog has an overarching effect, it is the sensation of being let in on someone’s interior weather report: not just the forecast, but the shifting cloud patterns, the brief breaks of light, the gathering storms. That Arnold makes space for rejection is less a fixation than an acknowledgment that to live authentically is to face, again and again, the places where we are not met in kind. What matters, the essays suggest, is what one builds in that aftermath.

In the end, Technomonk’s Musings offers neither an idealized self-portrait nor a manifesto. Instead, it is an ongoing ledger of encounters — personal, political, philosophical — kept with a level of care that suggests the act of recording is itself an act of connection. And that, perhaps, is the truer theme: not rejection, but persistence.

The Only Winning Move

“A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.” [The WOPR computer at the conclusion of “War Games” (1983).]

“War Games” is a 1983 movie starring Matthew Broderick, Ally Sheedy, John Wood and Dabney Coleman. I fell in love with this film the first time I saw it, at the State Theater in downtown Corvallis, during the first week of its release. A friend of mine had dropped by my apartment and said, “let’s go see ‘War Games’.” I hadn’t heard of it, but I said, “sure, ok.” (1983 is a couple of years before I first touched the keyboard and mouse of an Apple Macintosh, but I was, perhaps, influenced by this film, in the direction of my now long-time interest in computers.)

This is the story of a high school student, David Lightman (a stunningly-young Matthew Broderick, pre-Ferris-Bueller), an intelligent, but somewhat-naïve, underachiever with an interest in computers and computer games. He gets caught up in a dramatic, but mostly-unrealistic, scenario whereby he almost causes the end of the world by initiating WW III. The primary setting is Seattle, WA.

I watched this movie again this week (now available on Max) for maybe the tenth or fifteenth time. I think it’s totally fascinating to see the world portrayed as it existed in the Cold War era, before September 11th, and prior to the technology that we all now take for granted. How did we even exist in the pre-internet era of floppy discs and dime-eating pay phones!?

In search of the latest computer game by an outfit called ProtoVision, David searches for all the phone-modem-equipped computers in Sunnyvale, CA, and stumbles upon a Defense-Department machine called the WOPR (“War Operation Plan Response” – it’s pronounced like the Burger King sandwich, “whopper”). He ultimately finds a way into this machine via a back-door password left there by the original designer. The WOPR believes, therefore, that David is “Professor Falken,” its creator. Now posing as the Professor, he finds the game programs on this machine and elects to play, not chess, not poker, but rather something called “Global Thermonuclear War.” David chooses the side of the USSR in the conflict and initiates a nuclear strike on the US.

The machine interprets the entire activity, as “real” and, logically, takes steps to protect the US from the perceived attack. In the tense conclusion, during which time the WOPR seeks to find all the codes it needs to launch its nuclear-warhead-equipped missiles, David comes to the rescue at NORAD headquarters by requesting that WOPR play itself in an infinite number of tic-tac-toe games. Spoiler alert: World War III is averted when the WOPR “learns” that not only is that game nonsense, but any potential scenario leading to WW III is similarly fruitless: there’s simply no winner when, as it turns out, all outcomes lead to global annihilation.

As the film ends, the WOPR announces (in a semi-Hal-like voice) its assessment of “Global Thermonuclear War,” (to the relief of all at NORAD command): “A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

Interestingly, this is the same thought I had recently when a once-close personal relationship wound its way to a tortuous, scorched-earth conclusion. Ugh.

Soundtrack Suggestion

Don’t you understand what I’m trying to say

Can’t you feel the fears I’m feeling today?

If the button is pushed, there’s no runnin’ away

There’ll be no one to save with the world in a grave

Take a look around you boy, it’s bound to scare you, boy

And you tell me

Over and over and over again, my friend

How you don’t believe

We’re on the eve of destruction

(“Eve of Destruction” – Barry McGuire)

Generosity and Free Will

“I was trying to figure out what I should have already told you, but I never have. Something important, something every father should impart to his daughter. I finally got it: generosity. Be generous, with your time, with your love, with your life.” [From a terminally-ill, near death, Dr. Mark Greene, to daughter Rachel, during “On the Beach,” an episode of “ER,” May 9, 2002; emphasis mine.]

I wrote last time about my fall on the ice during the recent storm. As reported, I did not break any bones; however, the residual effects of the mishap continue to linger on. The trauma of the tumble seems to have taken up residence in my lower and upper back – as well as in my psyche. My spirits are quite low.

In the first two weeks after the storm, I had massage, physical-therapy, and Zero-balancing sessions – in addition to my regularly-scheduled therapy appointment. At this point, though, my recovery still has a way to go. I need significantly more time – andhelp- to facilitate my healing.

In questioning my life’s choices during this period of blueness, I reviewed an essay from February 2006 here on Musings entitled “Generosity.” I have had reason to reflect again on the meaning of this term and specifically its place in the context of friendship.

What am I talking about? Well, I now have reason to believe that what I had experienced as acts of generosity from a friend were, perhaps, deeds that had been misinterpreted by me. I now suspect that perhaps some kind of relational score-keeping had been in play. This has sent me even more into an emotional tailspin, leading me into a deeper examination of my own behavior; to wit: Who am I as a friend? Am I in search of some kind of reciprocity rather than act from a generous spirit? Am I generous enough with my love? My time? My energy? My life? Who am I, really? And, in this context, how am I perceived by others?